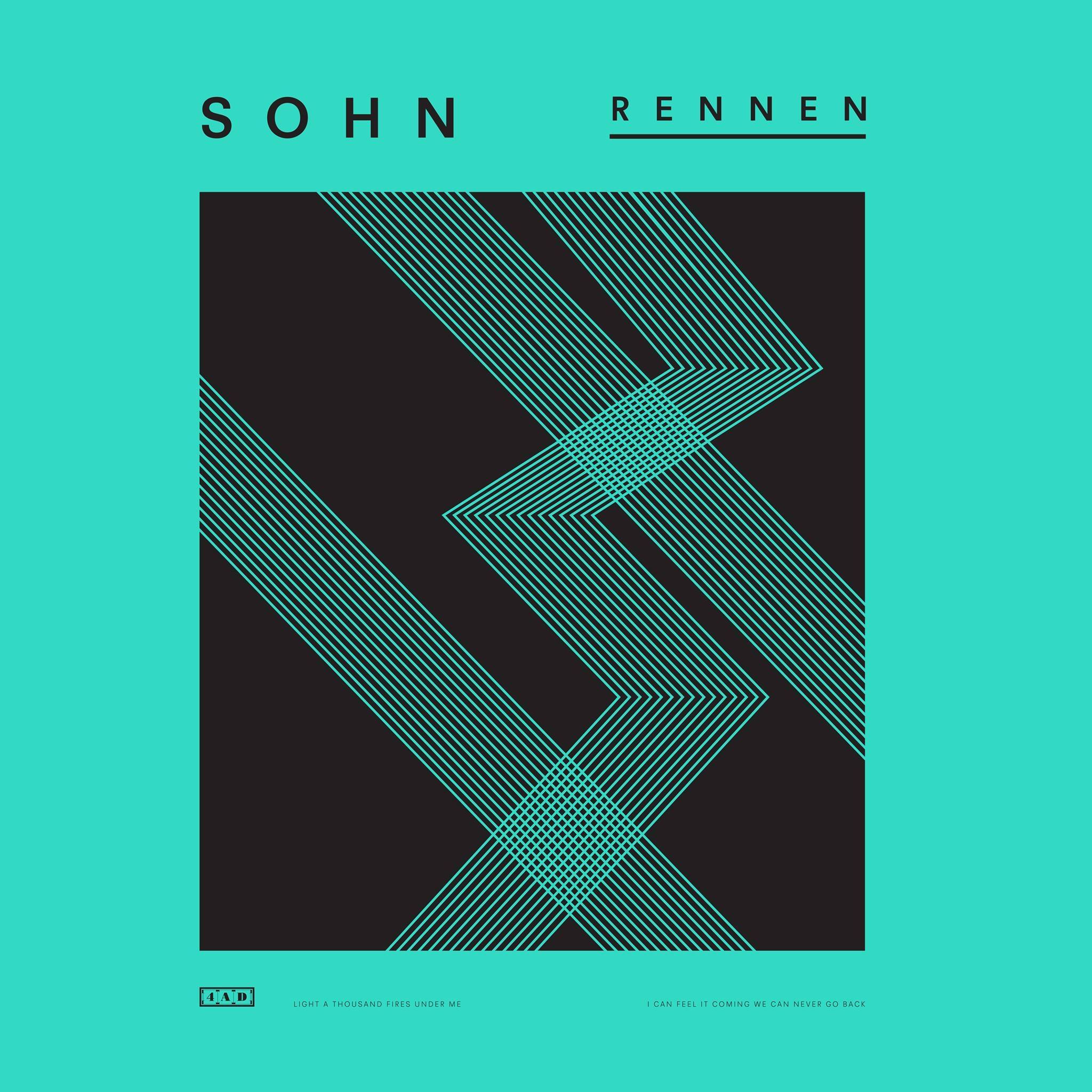

I’ll be touring this year with the British artist and producer, SOHN in support of his new album Rennen. Here are some initial 2017 Europe and North America dates. More info HERE.

13 February – VIENNA, Arena

14 February – MUNICH, Technikum

15 February – MILAN, Magnolia

16 February – GRAZ, PPC

17 February – BERLIN, Astra Kulturhaus

18 February – COLOGNE, Kantine

20 February – STOCKHOLM, Debaser Strand

21 February – OSLO, Parkteatret

22 February – COPENHAGEN, Koncertuset Studio 2

23 February – HAMBURG, MOJO

25 February – AMSTERDAM, Melkweg

26 February – BRUSSELS, Botanique

27 February – PARIS, La Maroquinerie

1 March – LONDON, Electric Brixton

19 March – DALLAS, TX, Trees

20 March – HOUSTON, TX, White Oak Music Hall (Downstairs)

22 March – ATLANTA, GA, Terminal West

23 March – CARRBORO, NC, Cat’s Cradle

24 March – WASHINGTON, DC, 9.30 Club

25 March – NEW YORK, NY, Warsaw

26 March – NEW YORK, NY, Irving Plaza

29 March – PHILADELPHIA, PA, Union Transfer

30 March – BOSTON, MA, The Sinclair

31 March – MONTREAL, QC, Fairmount Theatre

1 April – TORONTO, ON, Danforth Music Hall

3 April – CHICAGO, IL, Thalia Hall

4 April – MADISON, WI, Majestic Theatre

5 April – MINNEAPOLIS, MN, Triple Rock

8 April – VANCOUVER, BC, Rickshaw Theater

9 April – SEATTLE, WA, Neptune Theater

10 April – PORTLAND, OR, Wonder Ballroom

12 April – SAN FRANCISCO, The Regency

13 April – LOS ANGELES, Fonda Theater

14 April – COACHELLA

21 April – COACHELLA

20 May VALLE DE BRAVO, MEXICO, Bravo Festival

6/10/17 GELTENDORF, GERMANY, PULS Open Air

6/16/17 MANNHEIM, GERMANY, Maifeld Derby Festival

6/17/17 BARCELONA, SPAIN, Sonar by Day

6/24/17 BEUNINGEN, NETHERLANDS, Down the Rabbit Hole Festival

6/25/17 MOSCOW, RUSSIA, Bosco Fresh Festival

7/1/17 WERCHTER, BELGIUM, Rock Werchter Festival

7/5/17 CESENA, ITALY, Acieloaperto at Rocca Malatestiana

7/7/17 PADOVA, ITALY, Just Like Heaven at Anfiteatro del Venda

7/8/17 KATOWICE, POLAND, Festival Tauron Nowa Muzyka

7/13/17 CLUJ, ROMANIA, Electric Castle Festival

7/15/17 SOUTHWOLD, UK, Latitude Festival

7/16/17 FERROPOLIS, GERMANY, Melt Festival

7/22/17 WEISEN, AUSTRIA, Out of The Woods

7/27/17 WASHINGTON, DC, Merriweather Post Pavilion

7/28/17 BOSTON, MA Blue Hills Bank Pavilion

8/1/17 CLEVELAND, OH Jacobs Pavilio

8/3/17 KANSAS CITY, MO Starlight Theatre

8/6/17 MONTREAL, QC Osheaga Festival

8/7/17 DENVER, CO Red Rocks Amphitheatre

8/9/17 LOS ANGELES, CA, Shrine Auditorium

8/10/17LOS ANGELES, CA, Shrine Auditorium

8/11/17 SAN FRANCISCO, CA, Outside Lands Festival

8/19/17 BOCHUM, GERMANY, Ritournelle Festival

8/20/17 HAMBURG, GERMANY, Dockville Festival

9/30/17 SAN DIEGO, CA, CRSSD Festival

10/15/17 MIAMI, FL, II Points Festival