Along with beat placement, dynamics, and tones, the amount of swing in a groove is an element that has a tremendous affect on how a groove sounds and feels. When we first learn about swing, we tend to categorize a feel as either “swing” or “straight”, where a “straight” feel means all 8th notes or 16th notes (depending on the groove) have an equal space between them, and a “swing” feel means the notes that land on the &’s should line up with the 3rd note of the triplet subdivision. I think a lot of us learn swing this way because, truly, it’s a great way to teach that feel. However, as you advance as a player it’s crucial to understand there are actually different types of swing, and you should be able to recognize how they each impart a different vibe. While 8th note swing is crucial to jazz swing and blues shuffles, 16th note swing really shines in backbeat-based grooves. I chose to focus on the often overlooked 16th note swing groove.

I’m going to demonstrate 5 different swing feels, from straightest to swingest and point to some songs you can check out to hear these feels in context. Below each feel category is a YouTube playlist with some of my favorite songs and drummers demonstrating different 16th note feels.

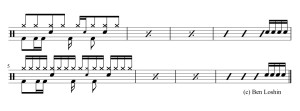

Here’s the basic groove I’m using in the video. There’s an 8th note hi hat pattern in the first 4 bars, then a short fill into a 16th-note hi hat pattern. Aside from some embellishments, the kick and snare stay the same throughout. Notice how the 8th notes on the hi hat in the first 4 bars don’t reveal the swing feel. This is because the 16th notes define the feel in this groove. Only the kick and snare notes that land on 16th note subdivisions (“e” and “a”) reveal the swing feel until the hi hat only goes to 16th notes. The key is to develop consistency through practice and really get comfortable with a feel before you bust it out on a gig. If you can’t hold these feels consistently throughout a song, you run the risk of sounding like you don’t know what you’re doing. Believe me, I’ve been there.

1. No Swing

This is pretty self-explanatory. The spacing between the 16th notes is perfectly even or very close to even.

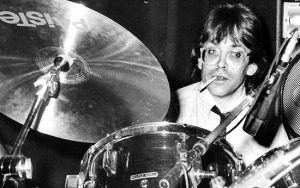

Note, however, that a human drummer playing a straight 16th groove can still feel a lot different than a drum machine playing the same groove. Compare the drum machine groove on The Human League’s “Don’t You Want Me” with Jeff Porcaro’s groove on Boz Scaggs’ “Lowdown”, and you’ll appreciate the differences. Although the patterns are almost identical, the two grooves feel very different. There’s a stiffness to the hi hat 16ths that works in “Don’t You Want Me”, but probably wouldn’t work as well in “Lowdown”. The kick and snare in “Don’t You Wan’t Me” are right on the beat, while Porcaro lays the snare back for a wider pocket. The point is, there’s more to the concept of feel than simply the amount of swing. Fun fact, “Don’t You Want Me” was actually the first song featuring the Linn LM-1 drum machine to go to Number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

2. Loose Straight

This particular feel fascinates me, and drummers don’t seem to talk about it much. I call it Loose Straight because it’s useful when you want to loosen your straight groove with a little hint of swing. You want to play a 16th groove, but put a little sauce on it, so to speak. The result is a mostly straight feel that doesn’t come across as stiff. It can be useful in the folk/Americana/classic RnB world where there usually aren’t as many programmed elements in the music and more room for a human feel. It’s also all over classic rock thanks to drummers like Ringo Starr, Levon Helm, Jim Keltner, and Jim Gordon.

If you just listen to one song from the playlist below, check out Jim Keltner’s playing on John Hiatt’s “Thing Called Love”. I’ll deviate here from the 16th note discussion because it’s such a good example of Loose Straight. The tambourine is playing an 8th note pattern that defines the feel of the track – not quite swing, definitely not straight, and grooving as hell!

The conga part in “What’s Goin On” is another great demonstration of Loose Straight. In the live version I posted in the playlist, there’s a piano and conga breakdown between 4:00 and 6:30 where you can really hear the Loose Straight 16th note subdivisions in Eddie “Bongo” Brown’s conga part.

3. In The Crack

This type of feel on a drumset, at least in a funk context, may have originated in New Orleans, with drummers like Zigaboo Modeliste and Johnny Vidacovich, fusing parade beats and Mardi Gras Indian rhythms with jazz. The result is a super greasy, dirty sounding groove. It’s a little looser than James Brown or Motown funk, but it’s not quite a triplet shuffle. People also use words like “swampy” and “slinky” to describe this feel.

4. Triplet Swing

As I touched on above, Triplet Swing is the type of swing most of us learn first, albeit in an 8th note context. If you play an 8th note shuffle, but put the backbeat on 3, you get a half-time shuffle, also called a 16th note shuffle. Notes that land on the “e” and “a” beats should line up with the 3rd note of an imaginary 16th note triplet. If you fill in the middle triplet subdivisions with ghost notes on the snare you get what’s known as the Purdie Shuffle, played by Bernard Purdie on Steely Dan’s “Home At Last” and “Babylon Sisters”. Variations of the Purdie shuffle were played by John Bonham on “Fool In The Rain” and Jeff Porcaro on “Rosanna”. The evenness of the triplet subdivisions gives this feel a rolling quality. Check out how triplet fills always work in this feel because the groove is based on triplets. Mitch Mitchell’s playing on “Little Wing” is a great example.

5. Tight Swing

Lastly, if you take Triplet Swing and compress the shuffle a little bit, you get what I call Tight Swing. In other words, the “e” and “a” beats are pushed closer to the next downbeat. The pattern approaches a doted 16th note, followed by a 32nd note, but it’s not quite that tight. Check out the skip beats on the bass drum in Questlove’s groove on D’Angelo’s “Devil’s Pie” and Brian McLeod’s groove on Ziggy Marley’s “True To Myself”.

In my next post, I’ll go into detail about how I practice these different swing feels. Stay tuned!